This is not an essay, this is a raw nerve…

I was recently directed to a couple of protests by students and graduates demanding ‘refunds’ for their degrees… this has been going on a while, and rears its head every couple of months, either around admissions time or graduation.

Now, while I’d love to boil this down to a 60 second InstaTok video, this has a lot to unpack. So, long blog post it is! Very long, in fact. There are a lot of ideas that need to converge together, and chatting to a camera for a minute in portrait mode just won’t cut it. Even on YouTube, this would require at least three costume changes.

It was the COVIDest of times…

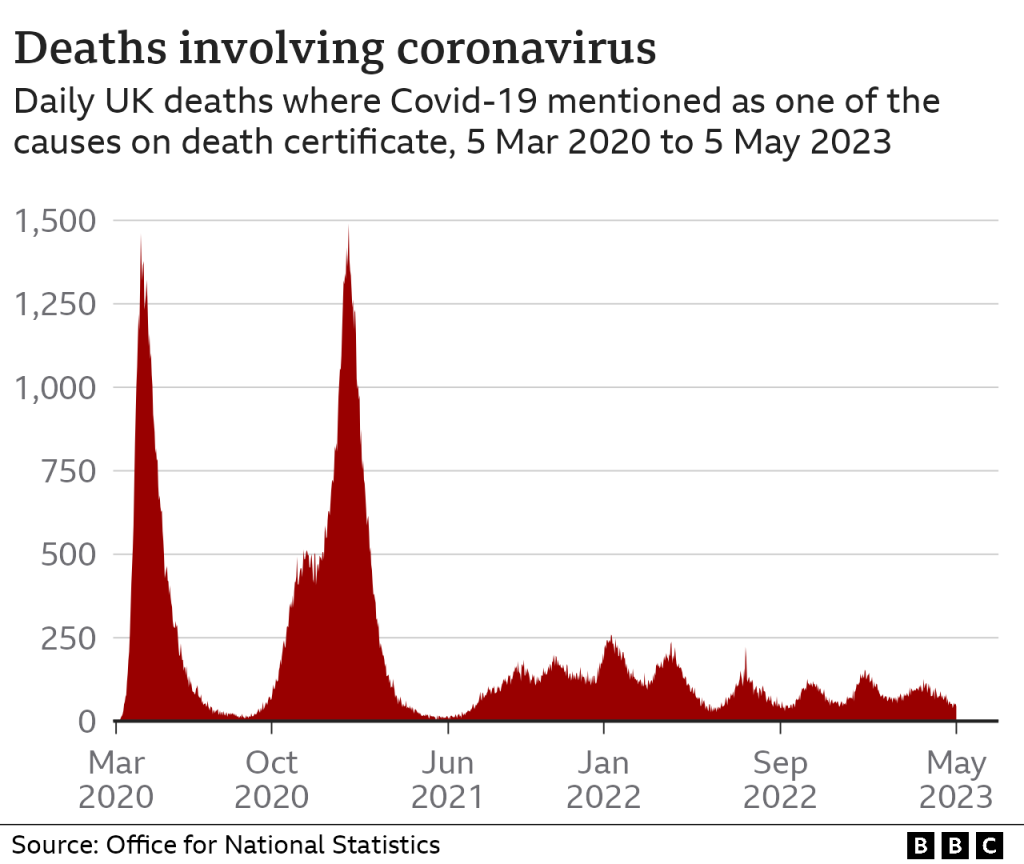

First, let’s address the low-hanging fruit pretty brutally. The main thrust of these demands for refunds is about online learning that happened a few years ago. Gee, I wonder why that happened…

Just to remind everyone: we were not doing all that for funsies.

I know people who died from COVID; people who lost family to it; people who were chronically disabled by it. Sorry you had some online lectures for a year. My friend’s 10 and 13 year old kids would love to hear about it; it’ll distract them from how their mother’s lungs strangled her to death while her body graphically and horrifyingly inflamed and deformed over the course of a month.

Yes, it’s a low blow, but that elephant in the room needs addressed, and now that’s over, we can ignore it going forward. Mostly.

Quality doesn’t grow on fees…

Let’s start at the top of the grievances about money.

In the UK, higher education comes in at an absurd £9,250 per year. Loans to cover living expenses are available in a similar order of magnitude. The end result is that you can be lumbered with a debt on par with having a full mortgage by age 21.

This is, of course, Not Good.

I am emphatically not pro tuition fee. But let’s also be very clear about how this system works: in the vast majority of cases, students have not paid anything. £9k of public money moves to universities (which is still between £2-5,000 short of funding a STEM degree, incidentally) and the student then has to pay it back.

At least, they have to pay some of it back.

The debt isn’t collected at a rate familiar to graduates in the United States, where it literally can be like paying off a second mortgage. There’s an income threshold that you must meet to be liable for repayment, and then you’re effectively taxed on income above that threshold. And you eventually stop paying it — either you clear it off, or it times out (after 30 years) and the debt is wiped. This system means that the government always makes a direct loss on fees. This is a graduate tax by another name

To be clear, the deal underpinning this is steadily being made worse, but this is entirely an issue of government policy (this will become a theme below…) and frighteningly little to do with universities.

Or is it?

Let’s back up a moment. That £9,250 figure is a cap. Universities are not a allowed to charge more than that, but they are allowed to charge less. When this cap was raised (and also when the original ‘top-up’ fee with a £3,000 cap was introduced) the idea was that it would introduce competition. Universities would charge less to attract “budget-conscious” students. Only the “best” universities would charge the full amount. Whatever “best” means, but that’s another discussion about the damage league tables have caused.

Why don’t universities do this? Why are the majority of courses £9k, and we don’t see these multiple fee tiers appear in reality?

To figure that one out, notice how the “debt” gets wiped, and that repayment acts as a tax. It doesn’t matter if you’ve taken on £7k per year of debt or £9k per year of debt (or £5k or £15k for that matter) your repayments and marginal impact to your take-home salary month-on-month is the same. The only change is the number of tax-free years you’ll have at the end as you rocket towards age 50. Or, more likely, you’ve simply changed the probability you’ll have any of those tax-free years at all.

So the benefit, the incentive, for a prospective student to pick a cheaper course is negligible. But, because the fee still represents the amount of public money transferred to the university, the downside is taking a course that has 25% or even 50% less funding. That’s a material loss to any student.

There is no incentive for students to take cheap courses, there is no incentive for universities to offer them. QED.

It’s also worth pointing out that this is exactly what people in the sector said would happen when the £9k cap was proposed a decade ago. To get alarmingly political, tuition fees are the perfect microcosm of how neoliberal-conservative politics repeatedly fail to understand economic incentives and money in general; the subject they claim to be experts and ‘grown-ups’ in.

Speaking of Conservatives, however, let’s just add that there are exceptions to the above. You can choose to pay up front to avoid the graduate tax. But if you’ve got around £10k going spare, and choose to spend it on tuition fees instead of, say, putting it in a high interest savings account for little Tarquin or, you know, just giving it to them each year, you’re an idiot. Paying up front is not a good investment at all. But I have been attacked on Twitter by a handful of people (that is, parents of students) who have done this. All Conservatives. All of them.

They’ll probably talk about it being a long-term saving, but again, you do not live in the Real World if you don’t understand the power of a £20-30,000 lump sum in cash, and instead opt to save £35 on a £2600 salary each month. They are not the fiscally responsible grown-ups they claim to be.

Anyway…

The psychological damage…

Again, to reiterate: with some outlying exceptions, the vast majority of students have not “paid” £9,250 per year.

BUT…

They are made to feel like they have.

The entire media ecosystem around UK universities inescapably focuses on this figure. Students feel that higher education is an investment, and one that must pay off. If I fuck up, even slightly, the words “I’m not paying £9,000 a year for this!” can be moments away. Even if you’ve actually paid diddly squat, you’re made to feel otherwise.

It’s a lot of pressure. For staff to live up to it (and to have it held to your throat every day…), and for students to live up to the investment.

To feel that you’re spending so much money, and must get as much from your degree as possible, get the ‘best’ university name on it, get the highest grade… all to get that job at the end so you can pay for it. When you’re told, constantly, that you’re lumbering yourself with the largest debt you’ve ever seen, a figure you likely have no salience for when you’re just 18, and then have to work to justify it… I cannot overstate the damage this has caused.

If you sat down to intentionally design a system that would demotivate and depress people, using all your knowledge of goal-directed behaviour and expectancy-value theory, you couldn’t intentionally come up with something this effective.

We’re seeing students less able to work, less resilient to setbacks, and all because they are under a relentless pressure to perform that they have to panic over every lost mark, and every little thing that makes university Not Worth It. And if it’s not worth it, why get up in the morning? Why open that textbook? Why even turn up to a lecture? It’s all a battle to min-max your time: get the highest marks, for the least effort, so that you can spend that time on other things (mostly working to afford rent, as we’ll see soon…).

Then let’s go back to the pressure on staff to make degrees “value for money”. We have to pack the curriculum with training, and job experience, and authenticity, and additional skills, skills, skills… Science curricula, already extremely information dense, need boosted further with employability… While nothing is cut to make room for it… All of which needs assessed and graded (or no one will do it) and takes up huge amounts of time.

No wonder there’s a “mental health crisis”.

If fees were less, then that pressure would be off, but instead it builds and builds…

And the other loan…

Less talked about than fees is maintenance.

This is the living expenses that students need to, you know, live while studying.

In our subject, students are with us for the best part of 15-20 hours per week.

Which will immediately trigger a number of people do say that it’s low! And students should count themselves lucky to have such a short week! Well, sparky, that’s contact time. That’s the time they’re physically in the room or the lab with me. We expect an additional hour per hour of self study. Time to revise, research, work on skills, write, edit along with the pre-reading watching required to make the much sought-after in-person lecture effective. That brings us up to a full adult portion of 35-40 hours of work. Less at start of the year, often far more as due dates loom. And that’s assuming the increasingly pressured timetable is efficiently spaced enough to allow for extra work between contact sessions, otherwise, much of the day is simply wasted.

This doesn’t leave much room for part time work. And, in fact, part time work doesn’t even cut it anymore. I know STEM students — fucking STEM students! — who need to treat their degree as secondary to their full time job just to make rent. Others need to live at home with parents, and commute — wiping out as much as two more hours each day in a car or (if they’re lucky because they can use the time to read) a bus, as well as severely limiting their options for where to study.

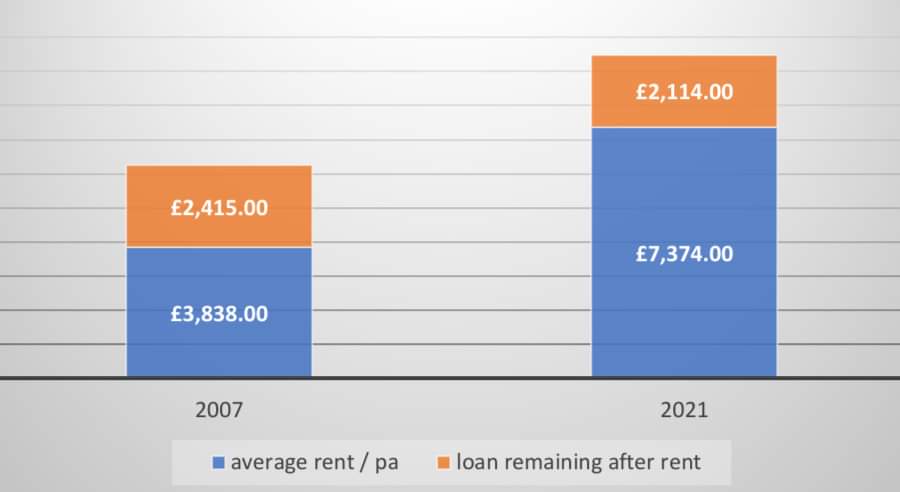

So, to get by, you need to take out the maintenance loan. Originally the only loan (that’s the one I’m still paying off, I think — as the SLC don’t have my current contact details but have no problems charging me) then a grant combined with loans for a little while, then all loan again. It’s all complex and all over the place. This, combined with fees, is what makes the total debt astronomical.

I also cannot emphasise enough that, of these two facets of student finance, the maintenance loan/grant is the bigger scam. While the fee at least goes to tangible things like the library, giving everyone a shiny copy of Office 365, journal access and, of course, paying me (and I like being able to afford food) the maintenance loan is largely a scam designed to offload as much public money as possible into the hands of private landlords.

The total average rent a student currently pays now exceeds the total maintenance loan I was eligible for in the mid/late 2000s. The increase in rent is between 7% and 10% each year depending on the location and the figures you pick, while typical national inflation averages 2-3% in normal circumstances.

When I hear students complain that maintenance hasn’t kept up with inflation, I have to point out that (medium-to-long term) this simply isn’t the case. It has exceeded it. What it hasn’t kept up with is rental costs. And it likely never could, because the instant that income gets a boost, landlords lick their lips and suck it up. Be assured, Tax Payers and fellow Old People: that pint you see a 19 year old quaffing on a Thursday night is not the thing you’re paying for.

There are a lot of reasons for this explosion in living cost. The general perpetual housing crisis being a key suspect. However, there are also strong contributions from private developers, hell bent on creating “luxury” student accommodation and charging a devastating premium for it. There’s also universities themselves, building increasingly shiny and expensive accommodation to attract students in a accommodation arms race to impress students (well, their parents, actually…) on open days.

This accommodation is still often complete trash, and not much better than the breeze-block hell I experienced a decade (or two…) ago. Student landlords are still the worst, and are absolutely raking it in even more.

To be extremely blunt, again, that students are angry about fees but rarely mention rent reflects very badly on us as educators. So much for us converting them to Marxist revolutionaries.

Selling the Experience…

That’s student finance, and you might have noticed that I haven’t addressed the grievances about ‘refunds’ much. That’s partially because I think the blunt and brutal foreword about COVID does a lot of heavy lifting there. But there is one word that keeps popping up when you hear people talk about why they were short changed:

“Experience”

This is possibly one of the more tragic shifts in recent years. We no longer provide higher education. We no longer provide degrees. We are purveyors of student experience.

You see it in the brochures, the prospectuses, the websites, the Instagram pages. All those photos of happy 20-somethings crowding around green fields and trees reading books in the glorious sunshine (which is funny because university terms happen over the colder months); the suspiciously clean nightclubs and luminous wrist bands; the enthusiastic smiling, glasses-wearing kid raising their hand in a lecture (never happens: the school system has made people too terrified of being wrong for that to ever happen). That sort of thing.

That’s the Experience. It’s the thing we’re selling. Or, at least, the thing we’re told to sell. Customer Satisfaction is the main KPI.

COVID shut that down. COVID shut a lot of things down. Notably it shut down the respiratory system of several million people, which is why I find this discussion offensive more than just irritating, but I digress. This discussion is only possible because the purpose of university has been shifted from education to “Student Experience”.

Now, to be clear, I’m not saying student experience isn’t important. Internally, we use it a a shorthand for mental welling, achievement, accessibility, equity, feedback and assessment, all of which are important. And, of course, there are things like learning to live on your own, with others, and growing to become a functioning adult with university acting a zone of proximal development. This is important.

But packaging this up as an “experience” for us to sell has caused some damage. Do I believe we “dumb down” courses to bribe students into ticking higher scores on the National Student Survey? No, I think that’s the Office for Students making shit up. But it does sometimes feel like that episode of Community, where Dean Pelton is desperately trying to court that high-roller prospective student with endless gimmicks — and the college suffers because they’re turning it into something it’s not.

We’re selling The Student Experience of shiny computer rooms and photogenic accommodation. And we have to sell more of it to pay for it, of course. And if we don’t sell it, the customers will go elsewhere to the institutions that paid for even shinier computer rooms and even more photogenic accommodation.

All that competition means more and more funds get diverted to endless initiatives that aren’t academic. We have these lovely cafes and “study pods”, we have trendy lighting and reclaimed wood tables, and you can get your book out while someone brings you fries served in a galvanized steel bucket — meanwhile, the ceiling in my teaching lab literally collapsed this week, and two research labs don’t have access to running water. In demanding The Student Experience, students have undermined the actual purpose of higher education.

We’ve sold university as a commodity that grants you a degree, so when we shut down lectures (which are not that pedagogically great, anyway) there’s a riot.

That’s not to blame individuals, per se. This is a systematic problem that has been building for the last twenty or so years. From the media environment telling you what student life should be about (Fresh Meat being the more realistic depiction) to government policy driving competition.

Maybe I’m just biased having worked in a place that did pretty well during the pandemic — having had access to a lot of online learning specialists who could make the rest best of it, resulting in us completely bucking the NSS trend in 2020. Maybe elsewhere was truly terrible. But I’m still convinced that the feelings of students who are demanding refunds are driven by these long-festering systematic issues, especially around the crushing demotivation of student finance, and the COIVD shutdowns were nothing more than a catalyst to highlight it.

So, about those refunds…

So, you had some online lectures. You had to MS Teams your way through tutorials while you kept your screen blank and refused to say anything. You want a refund.

It feels like students think a refund would be a £1000 sent immediately to their bank account. No it wouldn’t. You’d knock a few quid off your overall debt and it would be cancelled and wiped out 10 years before you managed to pay it off instead of 12 years. Paying the graduate tax for 30 full years is the case in all possible realities. Your agreement with paying this number back is with the government and the Student Loan Company.

Let’s say it’s even possible to get a “refund”. It would basically involve the university transferring several million pounds to the government. That’s it. It would make little sense in macroeconomic terms. The government receiving money isn’t like it collecting gold coins that it can then spend like it’s King John in a Robin Hood movie. Taxation and government income is basically about removing money from the system so that any public spending doesn’t immediately trigger hyperinflation. So, as a student, you would not be getting that money. But universities would suddenly have very real pounds missing from their budgets, which is hugely damaging t their ability to deliver the precious student experience to the next cohort of students.

It’s very easy for me to sound callous here, and very snarky, but at the end of the day we’re talking about people with an immense amount of privilege whining about something that occurred because literally hundreds of thousands of people were dying. I find that very hard to move beyond.

And I find it hard to deal with because this ire is directed at universities and teaching staff when, as I’ve hopefully illustrated above, the root causes of student finance problems are systematic and political. This is the result of decades of neoliberal and conservative policy trying to undermine higher education in the UK.

But who is the villain…

If you don’t mind me sounding like a conspiracy theorist for a moment, I’d say that this is exactly what the government wants. We’re stuck with a system that is inherently neoliberal, late-capitalist, and is slowly devolving into proto-fascism. Or possibly no “proto” about it. Universities are the enemy. It’s in the best interest of the government to get students to hate universities, and resent their education, and specifically target academic and teaching staff.

If I’m feeling feisty, I’d say think this is what the Office for Students was set up to do. Its priorities have repeatedly driven wedges between students and universities. While claiming to fight for students, it hasn’t really done much for them. Its policies and interventions have been based around non-issues like “freedom of speech” (of the “for me, not for thee” kind) and culture war nonsense. I can’t help but point out that feedback and assessment shows huge levels of dissatisfaction on the National Student Survey, but OfS haven’t set up a dedicated task force to address that — we’re far more likely to see them ask “Have you felt marginalised for saying trans people should be sent to death camps? Give us a call!” than anything else. And, already, we’re seeing independent reports remarking that OfS is simply acting as a political mouthpiece for the government. Rather than be horrified that students and universities are at war over fees and student experience, OfS is likely cackling to itself that all is going to plan and that this station will be fully operational by the time you’re rebel friends arrive…

Not good. Not good at all.

Ultimately, right-wing governments do not want educated people in their population. They do not want you to see education as a right, or something you can do because you enjoy it. They’ll dress it up, but ultimately it boils down to them viewing education as state-subsidised training that private companies don’t have to pay for. That’s why they’re happy for people to think universities owe them money, and not the government.

To try and bring it together, yes I do think a lot of calls for “refunds” is (mostly) uncalled for whining of middle-class privileged kids. But I do think it comes from a genuine place of frustration with the costs, both real (that is: rent and living) and perceived (that is: how you’re made to feel about tuition fees). That is something I can’t (and won’t) dismiss. In fact, we need to draw more attention to it.

The fees regime is… Bad. Make no mistake. But it’s something we have no control over. Most academics want education publicly funded, and for its benefits to be publicly realised. This halfway house, where we attempt to have public funding, but then badge it as a highly demotivating private debt, is simply unsustainable.

And that is something worth being angry about. Furious about, even. It should radicalise you, and make you demand change at the highest level, accepting no half-baked compromises. And it’s worth that feeling far, far more than any acute problems incurred in 2020.

There’s a lot here, but it’s also a wide reaching subject and I’ve missed lots out that could also be addressed. And because there’s so much of it, there’s no quick and easy solution.