Q “What did Crick and Watson discover?”

A: “Rosalind Franklin’s notes!”

Haha! Ha! HA!!

Ha…

I hate this joke. I absolutely despise it with a passion.

This has to be one of my most controversial and fart-in-a-spacesuit opinions: modern science communication, particularly with a feminist slant, is treating Rosalind Franklin way worse than she ever was back when she was alive.

There are a lot of other adjacent problems I have, of course. Science communication about women seems to be stuck in an “there’s only two chicks in the entire galaxy” loop: specifically Franklin and Skłodowska-Curie. Though that’s gotten better in recent years. We are just about allowed to talk about women who are still alive, for instance.

To understand my problem with science communication on Franklin, we need to look at this:

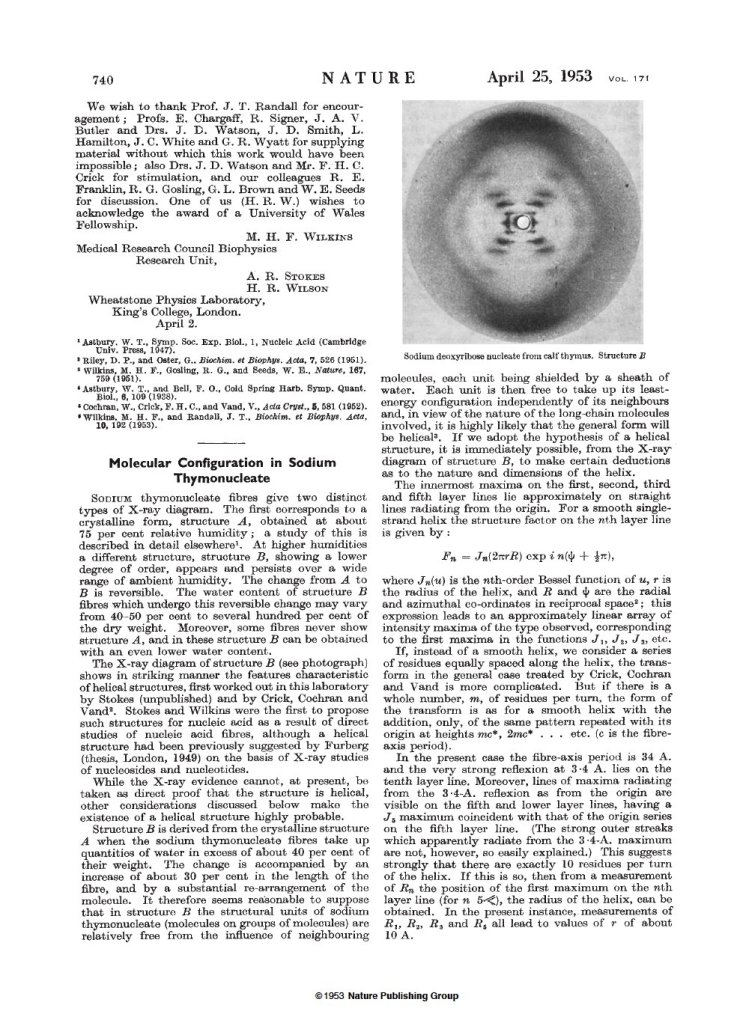

That’s ‘Molecular Configuration in Sodium Thymonucleate’, Nature volume 171, pages 740–741 (1953). The authors being Rosalind E. Franklin and Raymond G. Gosling. And if the date and journal seem familiar, that’s because it was published at the same time that Crick and Watson published their own famous paper – the third in the series was the one by Wilkins. If you turn the page after finishing Crick and Watson, you find Franklin and Gosling.

It’s behind a paywall, because reasons, and you absolutely should not buy it. But it’s also difficult (not impossible) to track down full, decently scanned copies, especially since using Sci Hub to download a scientist’s papers started being treated as a worse criminal offence than murdering them.

Few people seem to understand that this paper even exists, never mind what its content is. I can probably count on one hand the times I’ve seen someone communicate the science behind the structure of DNA and mention it or explore it.

On one level, it’s easy to explain why this is. This paper is dull, boring, technical, and tedious to go through. The X-ray diffraction world has come on so far since that it’s almost quaint to read. It’s of interest to specialists, as most papers are, and there’s a very limited amount of interesting things you can extract to make good pop-science fodder.

If you wanted to unpack it, you need to know a few things first… and I think many of those things fly in the face of the usual Sunday School version of the DNA story.

- You need to know these people were not “discovering” DNA — it had been known as a molecule for a very long time,

- You need to know that there are multiple forms of DNA, based on its level of hydration — so they weren’t “discovering the structure” of DNA as much as refining what was known about the specific forms of it,

- You also need to know that they weren’t even establishing that it was helical — again, something that had been known, or at least very strongly suspected, for a while (you can read that in Franklin and Gosling, above).

- Hell, you might need to know that Rosalind Franklin isn’t even the first female crystallographer overlooked in the DNA story — that unfortunate honour probably belongs to Florence Bell, working in the Astbury lab!

- You might also, wait for it, need to know that Frankling didn’t acquire the famous Photo 51 — that was Gosling, which raises awkward questions about supervisors stealing credit for their students’ work.

That was all done throughout the preceding 20-something years before Crick, Watson, Franklin, Wilkins and Gosling published their famous papers.

What Franklin and Gosling’s paper adds is the specific qualities of the helix in DNA: how quickly it turns, and the distances between atoms and groups. This is essential fine detail for building a structural model of it. We can hazard a guess at what it looks like if we suspect it’s helical, but unless this number matches up with the molecular model proposed by Crick and Watson in the preceding paper, we have a problem. We’re after all the fine detail at this stage.

And Franklin and Gosling did this with some exceedingly tedious, complex and dull mathematics that match up X-ray diffraction patterns to the molecular structure. And make absolutely no mistake: that’s hard work, it’s a big challenge. It requires skill, learning, practice, experience, and time plus dedication. This is highly specialist, complicated stuff.

And there’s the problem.

A lot of the popular perceptions of science are built on this idea of lone geniuses who simply see the Matrix and figure things out with instinct. If we’re lucky, we might see them working hard instead. But, on some level, it will always come back to individual personalities working alone and making grandiose discoveries in that instant. It’s far easier to get “Franklin discovered DNA single-handedly and two men stole all her work” into your head than to understand the decades of work, near-misses, and steady accumulation of evidence by hundreds of people that lead to the double helix. It ended with the Nobel Prize going to Maurice Wilkins, Francis Crick, and the abusive step-dad of DNA James Watson. They accidentally became the capstone on this massive scientific undertaking, it was never just them, and it never will be just one or two people working on problems of this size.

That’s what science is. It’s endless tedious accumulation of data to synthesise a conclusion that might be years in the making.

You might see the big speeches and announcements, and in the modern day the TikTok dances in the lab. But you don’t see the work. You don’t see the reading, the trial and error, the endless filling in of logs and lab books, ethical and COSHH applications (though that’s probably less applicable to the 1950s…) and more reading, and more questions, and more torn up notebooks of failure. That’s the part that isn’t talked about because it isn’t fun and it isn’t sexy. It’s tedious, and awful, and makes the job a job, not a “calling” or whatever people have described it as.

And if you dive into the work and contributions from Franklin, that’s what you find. Someone who has turned up, that has done the work, puts in the graft, and sticks her head down to prepare samples, acquire and process data, does the reading does the supervision, and writes it up at the end in excruciating technical detail.

In short, you find a competent, even masterful, scientist.

And she’s still reduced to a punchline of a joke.